By the Phoenix Warrior

Millions of people living with chronic illnesses face a harsh reality: they are often excluded from the disability sector and denied vital rights and support. This exclusion isn’t only unfair, but also a profound injustice that contradicts the core principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). When people with chronic illnesses are shut out, they lose access to legal protections against discrimination, essential accommodations at work or school, disability benefits, and healthcare tailored to their needs. Including chronic illness within the disability rights movement isn’t just the right thing to do legally and morally; it strengthens the fight for all people with disabilities. By recognizing our shared experiences of societal barriers and standing together, we build a more powerful, united force demanding a world where everyone, regardless of their health condition, can participate fully and with dignity. It’s time to break down this artificial barrier and ensure disability rights truly mean rights for all.

Beyond the Binary: Why Disability Rights Must Embrace Chronic Illness

Disability Rights Week 2025 arrives amidst growing recognition of disability justice, yet a significant population remains marginalized within the very movement advocating for rights and inclusion: people with chronic illnesses. Conditions like Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), fibromyalgia, Long COVID, autoimmune diseases like psoriatic disease and lupus, and severe mental health conditions are frequently excluded or relegated to the periphery of the disability sector in policy, activism, and resource allocation. This exclusion persists despite the clear mandate of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the lived realities of millions of people. It’s time to dismantle these artificial barriers and affirm that chronic illness unequivocally belongs within the disability rights framework.

Why the Exclusion? Roots of a Persistent Divide

The separation of chronic illness from the “traditional” disability sector stems from several intertwined historical, conceptual, and practical biases:

- The Myth of the “Stable” vs. “Fluctuating” Impairment: Disability rights frameworks, historically shaped by experiences of congenital or static physical or sensory impairments, often struggle with the fluctuating, unpredictable nature of many chronic illnesses. Symptoms like debilitating fatigue, pain flares, cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”), or periods of remission challenge rigid definitions of impairment. This variability is misinterpreted as less “legitimate” or harder to accommodate than visible, constant disabilities, leading to disbelief and exclusion.

- Medical Model Hangover & Gatekeeping: While the disability rights movement champions the social model (disability arising from societal barriers, not the impairment itself), chronic illness is often still viewed predominantly through a medical lens. Access to disability rights, benefits, and accommodations usually requires navigating complex medical gatekeeping, where diagnoses are contested (e.g., “medically unexplained symptoms”), treatments are lacking or controversial, and proving the constant severity required by outdated models becomes impossible. The NICE guideline controversy over ME/CFS, where evidence-based recommendations removing harmful therapies were initially withheld, starkly illustrates the power of medical disbelief to deny rights.

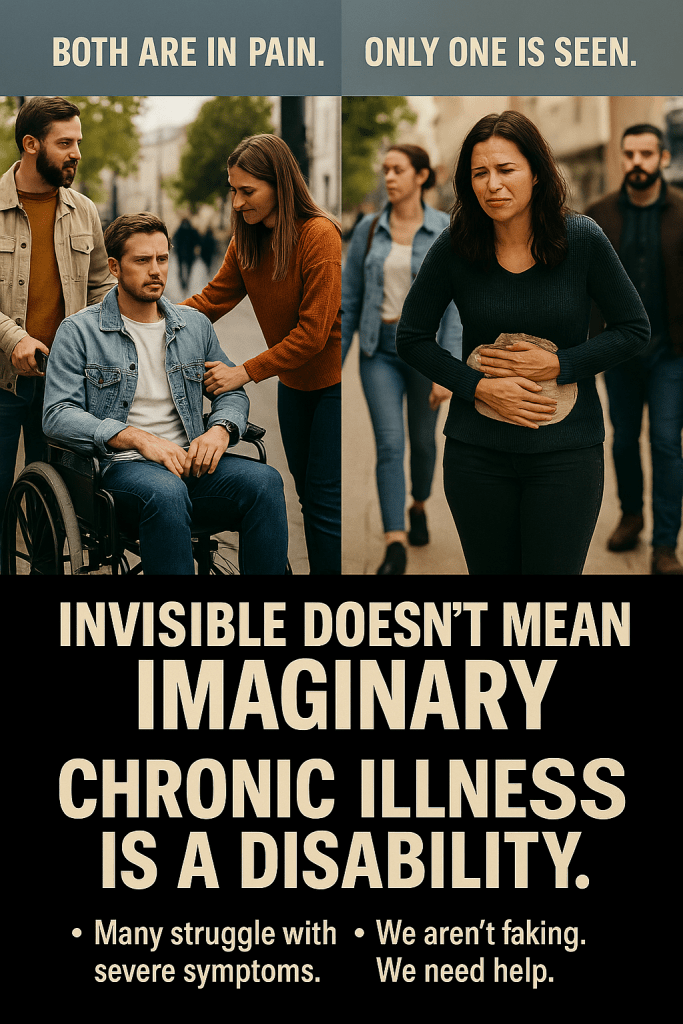

- The Invisibility Factor & Disbelief: Many chronic illnesses lack visible markers. Symptoms like profound exhaustion or cognitive impairment are internal and easily dismissed by others, including employers, service providers, policymakers, and even within disability communities. This leads to pervasive societal and institutional disbelief (“But you don’t look sick”), accusations of malingering, and denial of necessary adjustments and support 3510. Chronic Illness Inclusion’s research highlights systemic disbelief as a core barrier to recognition and rights 5.

- Resource Scarcity and Boundary Policing: In a context of austerity and limited resources (e.g., welfare benefits, accessible housing, personal assistance), there can be an unspoken, and sometimes explicit, fear that including the vast population living with chronic illnesses will dilute resources for others. This scarcity mindset fuels harmful “hierarchy of disability” narratives and boundary policing, excluding those whose conditions don’t fit a narrow archetype 13.

The UNCRPD Imperative: Why Inclusion is Non-Negotiable

The exclusion of people with chronic illnesses isn’t just a practical oversight; it’s a fundamental violation of the principles and definitions enshrined in the UNCRPD.

- The Definition Fits: Article 1 of the UNCRPD defines persons with disabilities as including those with “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” Chronic illnesses, by their very nature, are long-term health conditions causing impairments (e.g., reduced mobility, stamina, cognitive function, sensory processing). Crucially, these impairments interact with societal barriers (inaccessible work environments, inflexible policies, lack of remote access, discriminatory attitudes) to create disability 113. The impairment originates in health, but the disability arises from societal failure to accommodate and include.

- Shared Experiences of Structural Barriers: People with chronic illnesses face the same core disabling barriers as those recognized under the UNCRPD:

- Employment Discrimination: Significantly lower employment rates are attributed to inflexible hours, a lack of remote work options, disbelief about energy limitations (ELCI), and inaccessible workplaces. Chronic Illness Inclusion’s work directly links energy impairment to the disability employment gap.

- Inaccessible Healthcare: Barriers include physical inaccessibility, communication gaps (especially during brain fog), diagnostic overshadowing, stigma, and lack of provider understanding, leading to poorer health outcomes 5713. WHO data confirms that persons with disabilities face significant health inequities.

- Social Security & Poverty: Rigorous, often inappropriate assessments (such as the UK’s Work Capability Assessment) fail to capture fluctuating conditions, leading to the denial of essential benefits and plunging people into poverty.

- Social Exclusion & Stigma: Pervasive stigma, isolation, and lack of access to community life, social events, and transportation due to fatigue, pain, or inaccessible venues.

- Increased Vulnerability: Higher risks of poverty, violence (especially against women), and poorer overall health outcomes, mirroring patterns seen across the broader disability community.

- The Power of Intersectional Solidarity: Excluding chronic illness weakens the disability rights movement. It siloes experiences, fragments political power, and allows governments and institutions to divide and undermine demands for universal accessibility and inclusion. Including chronic illness strengthens the movement by:

- Amplifying Shared Struggles: Highlighting the universality of access needs (flexibility, remote participation, rest, and understanding) benefits all people with disabilities.

- Challenging Medical Paternalism: The fight for bodily autonomy and against forced treatment/institutionalization is shared.

- Promoting Inclusive Design: Designing for fluctuating, energy-limiting conditions creates more adaptable, universally beneficial systems (e.g., flexible work arrangements, hybrid events).

- Ethical and Health Equity Imperative: Excluding people with chronic illnesses from disability rights frameworks exacerbates health inequities. WHO highlights that persons with disabilities die earlier, have poorer health, and face significant barriers within health systems 13. Denying the disability label denies access to legal protections (such as anti-discrimination laws covering reasonable accommodations), support services, and targeted health interventions, thereby worsening these inequities.

Barriers Faced by People with Chronic Illnesses vs. Broader Disability Community

| Barrier Category | People with Chronic Illnesses (Especially ELCI) | Broader Disability Community (per WHO/Studies) | Shared Experience? |

| Employment | Inflexible schedules, disbelief re: fatigue, lack of remote options, “presenteeism” culture | Physical inaccessibility, communication barriers, and attitudinal discrimination | YES – Different manifestations, same outcome: exclusion |

| Healthcare Access | Diagnostic delays/denial (“MUS”), lack of provider knowledge, dismissal of symptoms, treatment barriers | Physical inaccessibility, communication gaps, diagnostic overshadowing, and lack of training | YES – Systemic failure to meet needs |

| Social Security Assessments | Assessments fail to capture fluctuation, focus on “good days,” and disbelief of subjective symptoms | Assessments often fail to capture diverse needs, focus on the medical, not the social model | YES – Inappropriate assessment criteria |

| Social Participation/Isolation | Fluctuating capacity, energy limits attendance, lack of rest spaces, and online access are crucial | Physical inaccessibility, lack of transport, communication barriers, and attitudinal | YES – Exclusion from community life |

| Stigma & Disbelief | “Invisible” symptoms doubted (“you look fine”), accused of malingering | Varied by visibility, but intellectual/psychosocial disabilities face high disbelief | YES – Societal lack of understanding & validation |

The Path to Inclusion: Dismantling Barriers, Building Solidarity

Recognizing chronic illness within the UNCRPD framework requires concrete actions:

- Explicit Recognition & Advocacy: Disability rights organizations (DDPOs) and governments must explicitly include chronic illness (including ELCI and contested conditions) within their definitions, policy work, and advocacy, citing the UNCRPD’s inclusive definition. Chronic Illness Inclusion’s efforts to frame energy impairment as a distinct access need are a crucial model.

- Challenging Disbelief & Medical Gatekeeping: Implement training for benefits assessors, healthcare professionals, employers, and within the disability sector itself on the nature of chronic illness, fluctuation, and energy limitations. Advocate for policies based on self-reporting and lived experience, moving away from solely medicalized proof of need.

- Embedding Flexibility & Remote Access: Champion “remote by default” as a core reasonable adjustment. Promote flexible work, education, and participation models that accommodate unpredictable symptoms and energy limits. This is not a lesser form of inclusion, but rather essential for many.

- Intersectional Campaigning: Build coalitions between advocates for individuals with chronic illnesses and broader disability rights groups. Jointly campaign on shared issues like social security reform (assessments based on real-world functioning), accessible healthcare, inclusive employment practices, and combating stigma. The fight against austerity cuts impacting disability benefits is a shared battle.

- Centering Lived Experience: Ensure that people with diverse chronic illnesses are meaningfully included in the leadership, decision-making, and design of disability policies, services, and research, as mandated by the UNCRPD’s principle of “Nothing About Us Without Us” (Article 25). Groups like Chronically Us demonstrate the power of peer support and advocacy.

A Call for Unity on Disability Rights Week

This Disability Rights Week (July 17 to 23), we must confront the uncomfortable truth that the disability rights movement, in its fight for justice, has sometimes replicated exclusionary practices. The separation of chronic illness from the disability sector is a historical artifact rooted in misconception, bias, and resource anxiety, not in the lived reality of disability or the clear mandate of the UNCRPD. People with chronic illnesses experience the same societal barriers, discrimination, and denial of rights as others recognized under the Convention. Their impairments, often fluctuating and invisible, interact decisively with disabling environments.

Inclusion is not a zero-sum game. Embracing chronic illness within the disability rights framework, guided by the UNCRPD, strengthens the collective fight for a world designed for all bodies and minds. It demands more adaptable systems, challenges deep-seated ableism and medical paternalism, and builds a more powerful, intersectional movement. We must dismantle the artificial walls, listen to the voices of those living with energy-limiting and fluctuating conditions, and make a truly inclusive disability sector where the full spectrum of human experience is recognized, respected, and afforded the rights guaranteed under international law. Chronic illness is disability. Their rights are our rights. Their fight is our fight. Let Disability Rights Week 2025 mark a decisive turn towards unity and inclusion.

Key References

Dawson & Szmukler (2014): Int. J. Law Psychiatry; CRPD’s applicability to psychosocial disability.

UNCRPD (2006): Defines disability inclusively; mandates non-discrimination (Articles 1, 5).

WHO Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities (2022): Highlights poverty/health gaps worsened by exclusion.

Chronic Illness Inclusion (UK) (2023): Research on energy impairment as a societal barrier.

German Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency: Legal recognition of chronic disease as disability.

Leave a comment